India is among the top three global economies in the number of digital consumers. With 560 million internet subscriptions in 2018, up from 238.71 million in 2013, India is the second-largest internet subscriptions market in the world. [1]

The Government of India runs large-scale benefits and subsidy programs for its citizens. To ensure accurate targeting of the beneficiaries, digital verification to eliminate duplicates, ghost recipients, and fraud. Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) was started on 1st January 2013. DBT is utilized to eliminate losses and inefficiencies in the disbursement of benefits and subsidies across wages, food, fertilizer, cooking gas, power, and other areas. Direct Benefit Transfer is already showing the changing landscape of the government-to-citizen (G2C) payments system.

Requirements

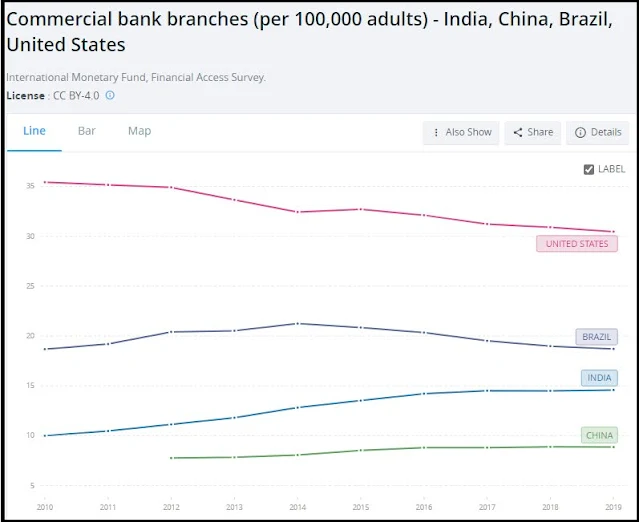

- To further expand the reach of such digital payment programs, banking infrastructure needs to be enhanced by ensuring sufficient bank branches, banking correspondents, the post office, and Common Services Centres to make it easier for citizens to access payments to them.

- Rural customers typically maintain low bank balances, are geographically spread out, and have low transaction volumes. Given the low levels of women's digital engagement, easy access to banking infrastructure for cash in-cash out services remains a necessary condition to enable. However, the private banking correspondent business model has chronically suffered from low profitability and a high level of agent attrition on account of unattractive remuneration.

There has been an attempt made by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) in the past for DBT readiness of states/UTs to pursue G2C and government to bank/business solutions through the use of ICT for effecting cashless in-kind transfers. (DBT_Presentation_NCAER (dbtbharat.gov.in).

Pros

- DBT eliminates inordinate delays, multiple channels & paperwork involved in the existing system.

- This is a better way to help the poor than providing them under-priced grain, fuel, and essential public services. A poor household with cash via DBT can access and choose a private-sector provider and not just be dependent on a monopolistic government provider.

- Targeting the poorest has the obvious advantage since the marginal value of money is highest since they have the least money.

- The per-person costs of delivering transfers have fallen rapidly in many places due to advances in last-mile digital payment infrastructure.

Cons

- The DBT model has been seen as a substitute for state action. The state has to build implementation capacity and grievance redressal mechanisms as many beneficiaries are used to interacting with frontline workers or local government officials for scheme-related grievances.

- While it may not be mandatory to link an Aadhaar Card with a bank account, for now, it appears that there is no escaping the process. Aadhaar seeding is necessitated for receiving Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT). This protocol followed by government officials has led to an increase in exclusion errors, denying genuine beneficiaries their entitlements.

- DBT system has no mechanism to strengthen transparency and accountability at the local level. Technical errors such as age, spelling, and a host of other data points plague the system. People with incorrect names, and mismatching dates of birth, end up unable to avail of any welfare scheme that they are otherwise eligible for.

- There has been an assumption that the economy will become burdened with these schemes leading to inflation and price distortion. Data again does not support this argument as it showed better economic participation and thus a net boost to the local economies where the schemes were implemented. DBT can be indexed to adjust with inflation.

- Complexity increases if Aadhaar is seeded in multiple bank accounts of beneficiaries. There are several cases like the money transferred to account holders died a few years back, and money could not get transferred due to the closure of accounts which are issues to be resolved with NPCI and banks.

Conclusion

DBT is no magic bullet as the reduction of poverty in India requires much more than solutions such as direct cash transfers. DBT is techno-enabled, transformational effort to fix the delivery system that is broken with corruption. Several studies have investigated the returns to investing in payments infrastructure relating to DBT and found them to be ‘large and positive’. In the new development, e-RUPI is launched by GoI to bring the ease and simplicity of UPI to the social security platform of DBT.

References:

1. Indian telecom services performance indicators, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, as of December 2013, September 2018, and

March 2018; Analysys Mason, as of January 09, 2019.